FEATURE: Preservation Hall and the bohemian French Quarter in the twentieth century

By Alison Fensterstock

Part 1 of 5

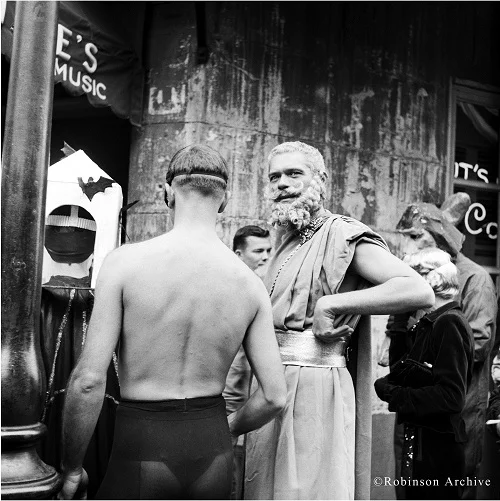

Preservation Hall opened in 1961, a welcome home base for the aging performers and listeners who prized their talents, experience and memories. The former art gallery drew a funky crowd: artists and beatniks, poets and travelers, rabid music fans and young musicians eager to hear New Orleans’ indigenous creation – jazz – from players who remembered its birth at the turn of the 20th century. The little building at 726 St. Peter stood nearly smack in the center of one of America’s oldest neighborhoods, full of grand old architecture and elegant restaurants. The Quarter was also home to vibrant immigrant communities, sailors in port for a few days with plenty of stories to tell, and young artists looking for community and cheap rent.

For more than a hundred years, the French Quarter has welcomed and nourished generations of freethinkers, artistic visionaries, creative entrepreneurs and free spirits. Preservation Hall was conceived in that rich and vital climate, and has gone on to become one of its venerable institutions. Read on to learn more about the poets, independent publishers, buskers, actors, eccentrics, activists and oddities that, like the Hall, have called the Quarter home.

Like New York’s Greenwich Village, by the early ‘60s the French Quarter already had a history as a hotbed of creative activity – particularly for those artists who marched proudly out of step with the mainstream. Painters, musicians, writers and unusual thinkers were drawn to the cheap rents and the laissez-faire culture of the neighborhood, with its vibrant cafe culture and busy, colorful street life. The Quarter’s first famous wave of 20th-century bohemia came in the years immediately following World War 1, when creative sorts like authors Sherwood Anderson and William Faulkner, painter Alberta Kinsey and photographer “Pops” Whitesell – whose studio was located at 726 St. Peter Street, which would later become Preservation Hall – made art, published writing, mounted theater productions and flouted Prohibition together.

That community birthed several impactful New Orleans artistic institutions, with varying lengths of endurance. From 1921 until 1925, the “Double Dealer” literary magazine published notable writers including the Quarterites Faulkner and Anderson as well as Djuna Barnes, Ernest Hemingway and Thornton Wilder. Between 1922 and 1951, the Arts and Crafts Club taught classes, held lectures and exhibited work by Picasso, Degas, Frida Kahlo, Salvador Dali and others. Le Petit Theatre du Vieux Carre remains at the edge of Jackson Square today, and celebrates its hundredth anniversary in 2016.

In “Dixie Bohemia,” his chronicle of the fertile ‘20s Quarter scene, author John Shelton Reed explains its eventual ebb with a familiar tale of the gentrification cycle: the artists had made the area attractive to tourists and high-society New Orleanians, who drove up real estate prices and crowded the galleries and cafes. Many members of the original creative set moved on. But the Quarter was far from tamed. As the twentieth century passed its halfway mark, America was on the cusp of seismic cultural and political change. At the dawn of the sixties in the French Quarter, art and activism intersected and were nourished in a singularly New Orleans way.