Photo Essay: Inside Bill Summers' Studio

World-renowned percussionist Bill Summers and his non-profit organization Klub K.I.D. was one of 20 recipients of the 2020 Preservation Hall Foundation Community Engagement Grants. In a previous Community Spotlight interview by local correspondent Tami Fairweather, Bill shared the work of Klub K.I.D. to train youth in the business end of entertainment, and how he found his spiritual calling as a global master of percussion and an ordained priest of the drum.

We asked Tami to visit with Bill again to document time spent in his longtime New Orleans studio through photos. Tami told us that when they first found a Sunday morning opening that worked with his schedule, she questioned whether Sunday was sacred to him--perhaps not the best time for a photoshoot. Bill declared that “every day is sacred,” and they went ahead with the plan.

Photos and Words by Tami Fairweather

The cockpit of Bill’s home studio is stationed in the second room of the raised shotgun-style house, where his office chair can roll swiftly from the computer keyboard to the sound mixing board, microphone to bookcase. The day before we met, he’d been working on this Shekere -- a traditional Afro-Cuban style percussion instrument made from a large gourd.

The Shekere is played similar to a Maraca, by moving and shaking the beads to hit the surface of the dried, hollowed-out gourd. Bill strings the beads by hand onto a loose net that he weaves around the outside of the instrument.

Bill has authored a book and co-authored another that offer rare documentation of rhythms used in ceremonial Batá drumming to call in the Orishas (spiritual deities of the African Yoruba culture, religion, and diaspora). “Sure, I play club dates and concerts, but I also play ceremonies,” he says.

The rhythms--which are literally prayers--need to be played in a specific order. Yet in sacred ceremony, you’d never see anyone reading these pages because they are committed to memory. So why document them? “To share,” Bill says, matter-of-factly, “in a language that white people can read too.”

Bill holds a photo of his “godfather” the late master drummer Esteban Vega Bacallao (“Chacha”) Iyalode Oshun and his wife, sitting inside their home in Matanzas, Cuba.

“He adopted me, and for 25, 30 years I studied under him.” Studying meant committing hundreds of rhythms to memory, and eventually being ordained as a priest of the drum in a week-long ceremony that took place after a yearlong initiation period.

On the last day of his initiation ceremony, Bill was presented to the Añá, the Orisha (spirit) of the drum, manifested in the form of Batá drums made by his godfather, Chacha. The drums themselves went through an initiation ritual before being gifted to Bill, and they now sit in the most sacred spot in the studio: on the top of his altar.

As a direct descendant of relatives who were born enslaved on a plantation upriver from New Orleans, Bill has done a lot of research about his family, including visiting the plantation where they once lived. He keeps bricks and pieces of glass found on the site of the former slave quarters on his ancestor altar, which is dedicated to the memory of all those who came before him.

In the telling of the Black history of New Orleans and Louisiana, there is no figure more legendary and important for Bill than rebel and folk hero Bras-Coupé who, as an enslaved person, was known by the name “Squire.”

“To me personally, if a person from New Orleans does not know who Bras-Coupé is, they don’t know the city they’re living in,” says Bill.

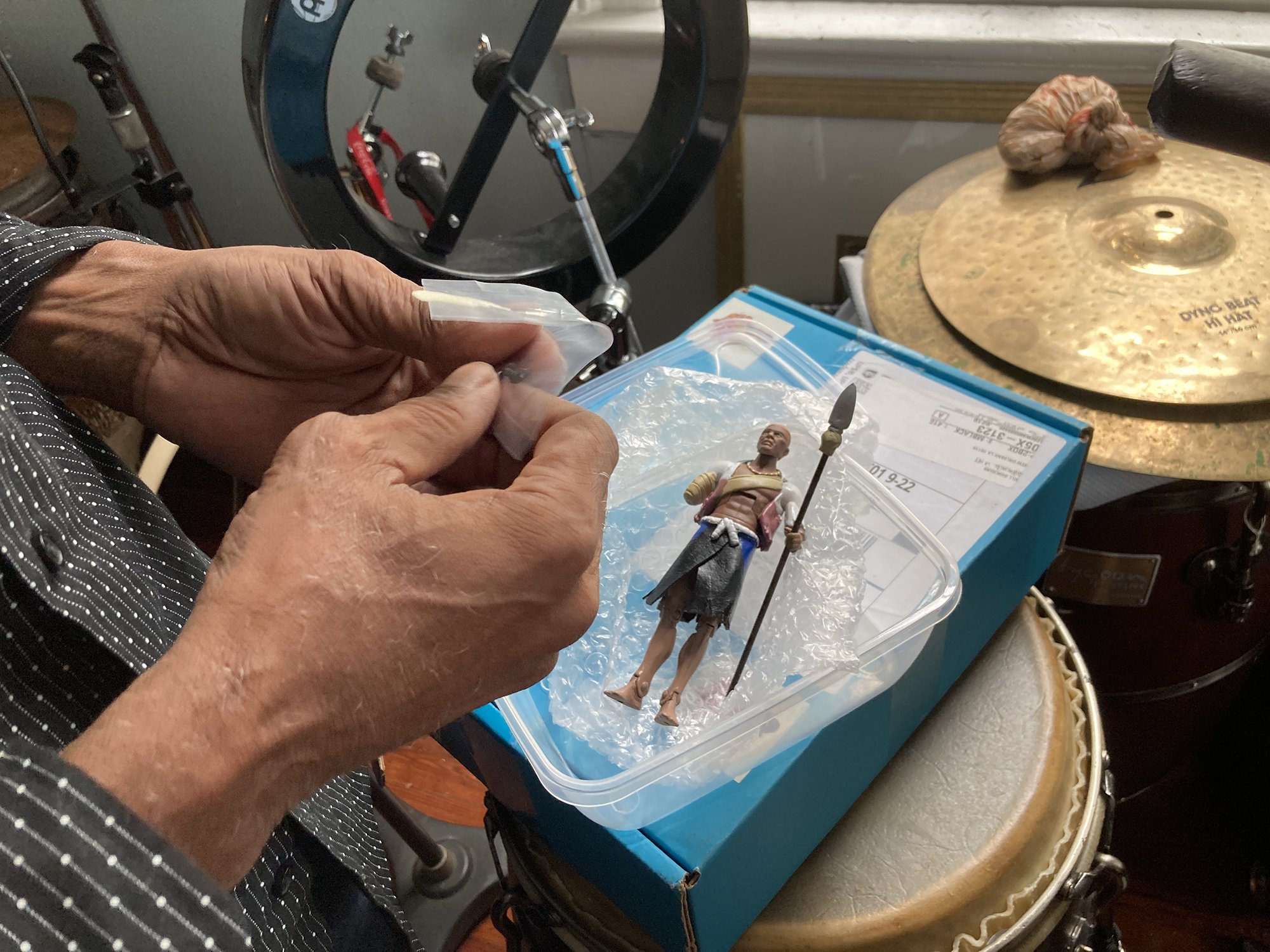

Bill commissioned an artist whose medium is superhero figurines to create one of Bras-Coupé, complete with his namesake missing arm (Bras-Coupé translates to “cut arm” in English). His arm was amputated as punishment for an escape attempt in the 1830s, prior to his successful escape to the swamp, where he became leader of a Maroon settlement.

To get up to speed on this superhero that Bill describes as “Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Ralph Abernathy, Medgar Evers, Frederick Douglas, and Marcus Garvey all wrapped into one,” Bill recommends “The Life and Legend of Bras-Coupé” by Bryan Wagner.

The book’s subtitle attempts to cover the depth and breadth of his status as a legend: “The Fugitive Slave Who Fought the Law, Ruled the Swamp, Danced at Congo Square, Invented Jazz, and Died for Love.”

It was a collaborative process with local artists, musicians, tribal members, spiritual leaders, and woodworkers that turned some discarded wood found in Congo Square into the “Freedom Drums.” They were Bill’s idea, though he doesn’t really know what moved him to do it. Only that “if this didn’t happen to them they would have died, been discarded or burned or tossed in the garbage.” But they were meant to live on, Bill says. (Watch this video on his website to learn more about their creation.)

An array of brightly-colored birds, horses, snakes, tigers, and other animal images on the drums were hand-painted by Bill after he had a dream that there were stories in the lines of the wood. The next morning he purchased some paint and slowly began to trace the grains of the wood in white, and as he did, the images started revealing themselves. He later filled them in with color.

Bill says that the music he loves most is about history, which makes sense given his natural proclivity to learn and then share what he’s learned (it’s what Klub K.I.D. is all about: “sharing, not teaching,” he says).

The history he shares goes deep. Translating the complexity of it all into rhythms you can feel is his genius. And also a whole lot of fun, like Bill himself.

Bill and Tami practicing the staging of a video shoot outside his studio.

Bill’s latest project is Forward Back, a collaboration with Scott Crowder Roberts (aka One Drop Scott). Their album An Ode to the Orishas: The African Powers is expected to drop in early 2022. You can give their first single a listen on Spotify here.